Understanding the practical and psychological barriers to diverse patient participation

Summary

Clinical trials are designed to study the efficacy of treatments for medical indications of all types. Many treatments have varying side effects and levels of efficacy among different patient populations. It is therefore crucial that clinical trials are representative of all patient populations, to identify how the effects of treatments vary before they are approved and prescribed.

Clariness conducted the largest survey on clinical trial diversity to date, which served as the foundation for the Short Report “Understanding the Practical and Psychological Barriers to Clinical Trial Diversity and Accessibility” on Dovepress. This survey aimed to investigate both the motivations and barriers to clinical trial participation of potential patients. We collected data from over 6,000 people living in nine countries, spanning a range of ethnicities, ages, genders, sexual orientations, and medical histories.

This blog, analyzes and summarizes the results of this survey, which led to one clear over-arching finding; insufficient trial enrollment, of both the general population and minority groups, is due to the presence of barriers, rather than an absence of motivation to participate.

The barriers to trial participation fell into two categories: practical and psychological, and this content examines each in turn. We show that the top practical barriers are financial and time constraints, and the top psychological barriers are a fear of receiving a placebo, a fear of side effects, and a lack of knowledge about clinical trials. We place these barriers in their historical and societal context, and suggest ways to overcome each of these barriers in turn. We aim this blog at the overall goal of increasing the diversity of patient populations in clinical trials and making trial participation more widely accessible.

Authors:

Shambhavi Chidambaram, Patient Insights Manager, Clariness

Joseph Yeomans, SVP Marketing & Growth, Clariness

Introduction

As part of Clariness’ commitment to increasing patient diversity and accessibility in clinical trials, we conducted the largest international survey diversity study in the pharma industry to date, designed to shed light on both the drivers of, and barriers to, trial participation.

We surveyed over 6,000 participants across nine countries: China, Germany, Poland, Malaysia, Mexico, United Kingdom, United States, Singapore, and South Korea. Nearly 4,000 participants were “true completers”, answering every question in the survey and generating more than 250,000 data points.

The volume and quality of these data gave us insight into both the practical and psychological barriers to participation in varied patient populations. These populations showed a diverse range of characteristics, including but not limited to:

- Age

- Country of residence and nationality

- Education level

- Family structure

- Medical indication and condition severity

- Insurance coverage

- Ethnic and gender identities

- Socioeconomic backgrounds

- Sexual orientation

A true opportunity to increase global trial participation and diversity

All of the findings put together lead to a clear, overarching conclusion: insufficient trial enrollment, of both the general population and underrepresented groups, is due to the presence of barriers, rather than an absence of motivation.

72% of global survey participants said that, in general, they would be willing to participate in a clinical trial, but only 24% of participants had actually done so before [1].

We found that groups typically underrepresented in clinical trials show a very high willingness to participate in trials:

- 70% of women [2]

- 73% of LGBTQ participants [3]

- 96% of black participants [4]

In interpreting the findings of our survey there are two important points that must be kept in mind. First, the participants that answered our survey may not be completely representative of the general population. Our sample is, by definition, data from participants who are more likely to answer a survey and have an interest in clinical trials for whatever reason: an existing illness, scientific curiosity, experience in healthcare, and so on.

This is why there are some differences between our data and similar data from the general population – less than 5% of the general population have participated in a trial, for example, versus the 24% in our survey. We emphasize, however, that this bias does not invalidate our findings. Rather, participants who are willing to answer questions and are interested in trials are exactly the population from which trial participants are likely to be drawn. Therefore, the conclusions we draw from these data are empirically grounded and relevant to the goal of boosting trial participation.

Second, our survey broke fresh ground in exploring why potential patients would or would not participate in clinical trials, and so did not include formal statistical analyses. Rather than looking for statistical significance, the conclusions from this exploratory survey would form the basis of future hypothesis-driven confirmatory research.

Our survey allowed us to better understand which barriers to trial participation affect different groups of participants, and how they vary by factors such as country of origin, gender identity, medical history, race/ethnicity, and healthcare systems. The challenges posed by this complex interplay of demographic factors, barriers to, and motivations for trial participation call for a correspondingly complex and diverse set of solutions. Such solutions aim to increase trial enrolment rates and trial diversity on a global scale.

As an example, financial reimbursement for trial participation seems like it may increase accessibility for patients from financially insecure backgrounds.

However, financial reimbursement alone cannot overcome the additional barriers potentially faced by financially insecure participants, these include:

- Inability to get time off work

- Cost of travel to the study site

- Lack of support in caring for dependent family members

In this scenario, a combination of decentralizing or digitizing physical site visits, financial reimbursement, and travel arrangements might together increase the participation of patients from this socioeconomic background.

The largest barriers to trial participation

In this blog we highlight the most significant findings of our international survey. Using these data and our extensive existing knowledge, we provide analyses and possible solutions to improve trial diversity and accessibility.

The following key question allowed us to identify barriers to clinical trial participation that affected patients across all countries, demographics, and psychographics:

Which three of the following reasons would be most likely to prevent you from participating in a clinical trial?“

We categorized the barriers into two groups: practical and psychological

Practical barriers to trial participation were to do with time, money, and the difficulty of traveling to a study site. Psychological barriers were mainly about a fear of the unknown, and a lack of knowledge of what would happen in the trial and the effect of taking the medical treatment being studied.

The sheer volume and depth of these data and the ability to group responses by indication, country, and several other factors, means this blog covers the survey’s top-level findings, grouped by country, socioeconomic background, and several other factors.

Practical barriers

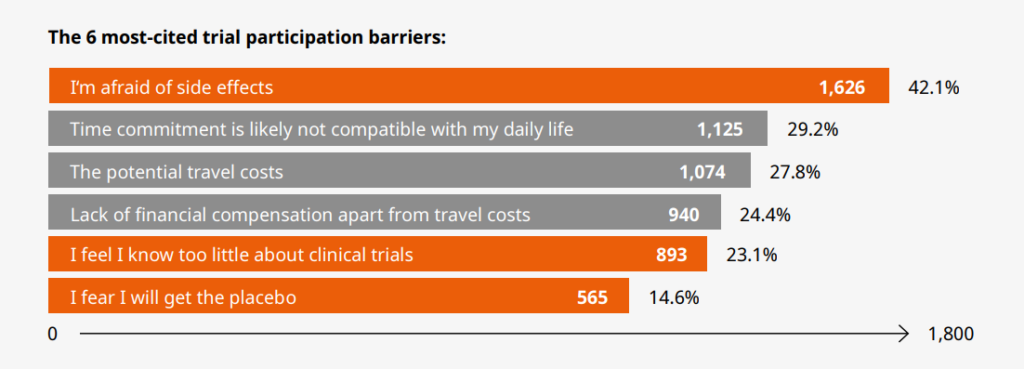

Participation in a clinical trial can last several months to years and may require multiple visits to a study center. Our data indicate that practical barriers to trial participation are rooted in a lack of time, money, and access to the trial. In this section of the blog, we describe the three most reported practical barriers overall and suggest how they could be addressed. The three largest practical barriers cited by participants were as follows:

A lack of sufficient time and money to participate in a clinical trial is more likely to be a barrier for participants from marginalized or disadvantaged backgrounds. In other words, who has access to clinical trials can be dictated by existing societal inequalities. Our survey found that LGBTQ+ participants, financially insecure participants, and ethnic minorities – specifically Black and Hispanic participants – cited practical barriers more frequently than participants from other communities.

In this section of the blog, we outline the three most reported psychological barriers overall, provide the context in which these barriers exist, and suggest what study organizers should consider to overcome them.

Time commitment

Approximately 30% of participants cited as a barrier the inability to commit the time to participate in a trial. This barrier is more complex than just the availability of a few spare hours per week or month. The time spent by a patient traveling to the study center, completing required assessments, receiving the treatment, and traveling back results in time taken out of their paid employment, housework, childcare, or the care of family members. Any or all of these might not be feasible to manage.

Overcoming an inability to commit time to a clinical trial

The time commitment being incompatible with a patient’s daily life might be a question of either willingness or ability. For an unwilling patient, the time required to participate in a study may not seem worth it if their illness is not very severe, or if the treatment they already take is sufficient for their needs.

For such patients, trial participation may not fulfill a need of their own, but might satisfy an altruistic desire to contribute to society or the advancement of science. This was cited as a motivation to participate in clinical trials by 40% of survey respondents overall, and even 19% of people who did not want to participate in trials cited this as a potential motivation to participate. Reminding potential patients of the altruistic aspect of trial participation might overcome their unwillingness to commit the time to a trial.

The problem of the inability to commit time is a more complex one to solve. A great deal of the time required to participate in a clinical trial is spent traveling to and from the study center. One possible way to deal with this is to work as closely as possible with the patient to schedule on-site appointments that work with their schedule – weekends or outside of their normal work hours.

Another solution would be to make as much of the treatment as possible accessible from home. For example, if a trial requires a patient to have regular check-ins with the health care professionals conducting the trial, these check-ins might be done remotely; or the patient could be allowed to self- administer the treatment at home, for which they might need some initial help.

The financial costs of participation

Going to a study center to participate in a clinical trial carries both direct and indirect financial costs for a participant. Out of the three most cited practical barriers to participation, our survey respondents cited two distinct but closely related financial barriers: “Potential travel costs” by 28% of participants; and “A lack of financial compensation apart from travel costs” by 24% [7].

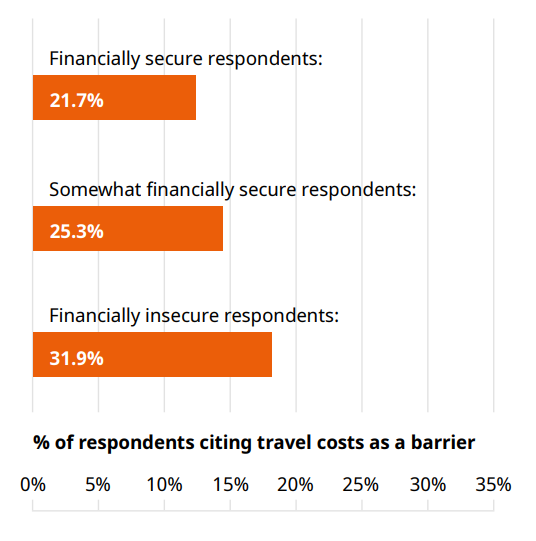

The direct cost of travel to a study site might be train and bus tickets, or the cost of fuel for a car. As one might expect, travel costs were cited as a barrier more frequently by participants with lower levels of financial security, as shown in Figure 2.

The indirect costs of travel are not as clear-cut and could vary greatly from person to person. Traveling to a study site takes up time that is not available for other activities, which may require a trial participant to pay someone else to do – hiring a babysitter for childcare, elder care, or pet care for example.

Indirect costs might even be the need for additional care of the patient due to the physical toll of travel. All of these reasons may contribute to the fact that nearly a quarter of survey respondents found a lack of financial compensation a barrier to trial participation.

The less financially secure a respondent felt, the more they cited travel costs as a barrier

A financial privilege may reinforce other societal inequalities

Participants from marginalized groups such as the LGBTQ+ community or some racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to be financially disadvantaged as well, and so find the costs of trial participation prohibitively high. Thus, how much of a barrier to participation financial costs are can vary by several related factors: country of residence, being part of a marginalized group, and of course financial security, as our survey results show.

- 34.7% of bisexual/pansexual participants, and 44.6% of homosexual participants, cited a lack of financial compensation as a barrier, compared to 28% of heterosexual participants. Only 17% of asexual participants and 23% of participants who identified as queer cited a lack of financial compensation as a barrier, but we do note that these demographics had low sample sizes. [9] This indicates that the interaction of an LGBTQ+ identity and financial privilege is a complex one, rather than marginalization leading to less financial privilege in a straightforward way.

- 53.9% of Black participants cited a lack of financial compensation as a barrier, whereas only 24.3% of Caucasian participants did [10]

- 39.1% of survey respondents from the USA cited a lack of financial compensation as a barrier, compared to a global average of 24.4% [11]

Within the USA, financial security varied by race and ethnicity. Hispanic, Black, and Caucasian participants made up the majority of survey respondents, and the percentage of these respondents that called themselves financially secure were as follows:

- Hispanic: 3.8% [12]

- Black: 8.4%

- Caucasian: 13.5%

Overcoming the barrier of the financial costs of participation

At the time that patients are pre-screened for a study it could be made clear to them that financial reimbursement will be offered. Overall, 28% of survey participants cited “Earning extra money” as a motivation to participate in trials, a strong indicator that reimbursing patients might support retention.

Our survey showed that marginalized communities such as black and LGBTQ+ people were more likely to cite a lack of financial compensation as a barrier to participation. This indicates therefore that communicating the information that financial reimbursement will be given to patients might also have the desired effect of boosting the number of patients from marginalized groups.

The inclusivity and accessibility of clinical trials to participants who need financial reimbursement is more important than ever for this reason. Indeed, patients who face no financial barriers to trial participation may be less sick than the average patient who will ultimately take the treatment being studied once it is widely available. Wealth correlates with general health, potentially skewing the results of a trial that is inaccessible to those at a financial disadvantage.

Studies have long shown that higher wealth correlates with improved general health. For this reason, patients who face no financial barriers to trial participation may be less sick than the average patient who will ultimately take the treatment being studied once it is available on the market, potentially skewing the trial results. For this reason, the accessibility of clinical trials to participants who need financial reimbursement is very important.

Psychological barriers

The reluctance to participate in trials is often due to psychological barriers, typically driven by a person’s expectation of what might or might not happen to them, as well as past experiences. While practical barriers can have relatively straightforward solutions, psychological barriers are often rooted in deep fears, which make them challenging to identify and overcome.

Such fears can come from a history of bad experiences with doctors and healthcare systems, which disproportionately occur in marginalized communities. For instance, survey respondents identifying as non-binary consistently reported greater dissatisfaction with their doctors than any other gender identity:

- 56.5% had trouble finding doctors that fit their requirements [13]

- 50% reported that their doctors were insensitive to them

- 54.3% said they were afraid to visit doctors or hospitals

- 37% felt like their doctors don’t listen to them

By contrast, past experiences with clinical trials themselves seemed to be overwhelmingly positive across the board, with 91% of participants who had ever been in a clinical trial saying they would be willing to participate again in the future. [14] Essentially, psychological barriers to trial participation function against a background of generally high willingness to participate.

While these barriers can be more difficult to address and overcome, doing so is vitally important. These efforts will help to diversify trial patient populations and make them more representative of the global communities that will eventually receive the treatment being studied.

In this section of the blog, we outline the most reported psychological barriers overall, provide the context in which these barriers exist, and suggest what study organizers can do to overcome them.

The three most commonly reported psychological barriers by our participants are:

- Fear of side effects (42.1%) [15]

- Lack of knowledge about clinical trials (23.1%)

- Fear of receiving the placebo (14.6%)

Fear of side effects

The single biggest barrier to trial participation was a fear of side effects, cited by 42% of our survey participants. There was little difference between patients with and without a chronic illness in how often this barrier was cited. What did seem to make a difference, however, was whether a patient had previous experience of participating in a clinical trial.

- 46.9% of participants who have not participated in a clinical trial said they are afraid of side effects [16]

- Only 28% of participants who have participated in a clinical trial said they are afraid of side effects

It would seem, therefore, that a fear of side effects is at least partially a fear of the unknown. This could be addressed, if not by experience, then at least by information.

How to overcome a fear of side effects

By the time a patient enters a clinical trial, some of the potential side effects of the treatment may be known. Most patients enter a trial in phase II or phase III, where the largest number of volunteers are needed. At these points the medical treatment has already been tested on dozens or even hundreds of patients, helping the study researchers figure out the treatment’s side effects and refine their research methods.

Consequently, by the time most participants enter a trial, they are not plunging into the unknown. Informing patients who are fearful of side effects that clinical research is done using a careful, step-by-step process might go a long way towards reassuring them. Patients must know not only what might happen to them, but that they will be respected and taken care of during the trial.

Lack of knowledge about clinical trials

Our finding that a desire for more knowledge plays an important role in the willingness to participate in a trial was a robust one, supported by the answers to multiple questions. From a trial participant’s point of view, their body is intimately involved in a long and complicated procedure, of which they see and understand only a small part.

- 23.1% of participants cited a lack of clinical trial knowledge as a barrier to participation [17]

This number varied from country to country and was highest in Malaysia, where nearly 50% of survey participants cited a lack of knowledge as a barrier [18]. “Learning about my condition or the treatment” was the top motivation to participate in a clinical trial, cited by 42% of survey participants. Among those participants who were unwilling to participate in trials, 31% cited a lack of knowledge about trials as a barrier, and 32% said they did not have a good understanding of clinical trials [19].

Informational materials are a good place to start in addressing a lack of knowledge

In medicine and especially medical research it is not merely the consent, but the informed consent of the patient that is a foundational principle. However, there will always be a vast difference between doctors and patients in the information they possess: information about medical conditions, treatments, and the associated clinical trials. Patients are fully aware of this fact: 37% of our survey participants said they relied on doctors as a source of advice about clinical trials. Providing trial participants with patient-friendly, non-technical informational materials that explain how a trial works is a good place to start in meeting a patient’s need to understand what is happening to them. The results of our survey indicate that such a measure would be likely to increase trial participation and ensure truly informed consent.

Fear of receiving the placebo

A typical trial compares a “test group” receiving the experimental medical treatment against a “control group” receiving either the best available existing treatment on the market or a placebo. This is to guard against a well-known phenomenon called the “placebo effect”, when a person feels better purely because they think they’ve received a medicine, when, in fact, they have not. Most trials are “double-blind”, meaning that neither the patient nor the doctor administering the treatment knows whether a patient is receiving the placebo or the real treatment. If the treatment works, those patients receiving the real treatment will do better than the ones receiving the placebo. It is critical that patients must not know what they are receiving to rule out the placebo effect as the reason they get better.

Around 15% of survey participants cited fear of getting the placebo instead of the real treatment as a barrier to trial participation. This is far from a majority, but still the third most-cited psychological barrier in our survey. Simply not addressing this concern then, could potentially reduce the potential patient population by up to 15%.

How do you address a fear of the placebo in a placebo-controlled trial?

When a trial compares a treatment to another treatment already on the market, communicating this clearly to potential patients may go some way towards alleviating their fear that they will go completely without care for their illness. That said, the possibility of receiving a placebo is always present in trials comparing treatments to placebos.

A way to potentially address the fear of receiving the placebo is suggested by the answer to another question in our survey, “What would motivate you to participate in a clinical trial?”.

- 39.5% of respondents cited “Contributing to the well-being of society or the advancement of science” as a driver for trial participation [20]

This makes altruism the second-most cited motivation to participate in a trial. The placebo group is an indispensable part of a clinical trial that may bring a critically-needed treatment to the market. Communicating this fact to potential trial participants may help overcome their fear of receiving the placebo as they would understand that, should they receive a placebo, they are still contributing to the development of a treatment that could eventually help them and other patients with the same condition.

Marginalized populations & willingness to participate

A majority of survey participants were willing to participate in clinical trials across different racial/ethnic groups, gender identities, countries, and age groups. This is a remarkable finding, given that many marginalized communities have historically experienced neglect or even exploitation in medical research.

Women make up half the population of the human species, and yet clinical trials have historically excluded women and treated men as the default. Even today, clinical studies focused on women- specific conditions or outcomes are chronically underfunded. In another example, the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s killed over a thousand gay men in the USA over two years, until the US Congress finally yielded to activists and passed a bill to allocate funding to AIDS research and clinical trials.

In the history of research with marginalized racial/ethnic groups, a famous example is the Tuskegee syphilis trial, wherein 400 black men with syphilis had the known cure for the disease, penicillin, deliberately and non-consensually withheld from them, supposedly to study the course of the disease.

Despite this history, our survey respondents from minority groups showed a high willingness to participate:

- 70% of participants who identified as women expressed an interest in participating in a clinical trial [21]

- 73% of LGBTQ+ participants expressed an interest in participating in a clinical trial [22]

- 96% of Black participants expressed an interest in participating in a clinical trial [23]

There is still clearly an unsatisfied need to include marginalized communities in clinical research, but our survey shows that there is also an unsatisfied desire in such communities to be included.

We now have a better understanding what barriers prevent this desire from being fulfilled and can begin to take steps to carry out inclusive and accessible clinical research and break those barriers down.

Key takeaways

If our survey results and observations can be condensed into one overarching finding, it would be that insufficient trial enrollment, of both the general population and minority groups, is due to the presence of barriers, rather than an absence of motivation.

We summarize the measures discussed above to that can be taken to address these barriers.

Practical barriers

| Barrier | Possible solutions |

| The time commitment is likely not compatible with my daily life | 1. Reducing the number of on-site visits required 2. Exploring making remote visits possible 3. Running feasibility surveys to understand points such as: the minimum number of site visits required to each the study goal; patient-specific needs; the right balance for patients in the trade-off between willingness to participate and the medical need for side visits |

| The financial cost of participation | Making clear if reimbursement is available as early as possible in the patient’s enrollment journey |

Psychological barriers

| Barrier | Possible solutions |

| Fear of side effects | Creating patient-friendly material giving background information about the trial, including information such as: 1. The treatment has already been tested in humans; many side effects are known, as well as how likely they are to occur 2. If side effects do occur, the patient will be well taken care of 3. If the patient wishes to withdraw from the study, their decision will be unconditionally respected |

| Lack of knowledge about clinical trials | Providing as much information as possible through patient-friendly FAQs and explainer videos at every step of the patient’s enrollment journey |

| Fear of receiving the placebo | 1. Emphasizing the altruistic and scientific value of study participation in the materials given to patients 2. Reminding patients that they are part of a bigger scientific discovery, and whether they receive the placebo or not they are helping bring a treatment to the market that they, and others with their condition, could access one day 3. Using testimonial and quotes from other patients on the part they can play in the development of a new treatment |

Are you striving to increase enrollment and trial diversity?

The insights shared within this blog can be applied to trials of any indication across the globe, if you would like to know how to increase your trial enrollment of all patient populations, contact us here.

References

[1] Out of 3,858 true completers [2] Out of 2,227 women [3] Out of 587 LGBTQ+ participants [4] Out of 102 black participants [5] Out of 3,858 true completers [6] Percentage numbers in all three points are out of 3,858 true completers [7] Percentage numbers are out of 3,858 true completers [8] The number of participants in each of these categories was – financially secure: 364; somewhat secure: 1,602; financially insecure: 1,709 [9] The number of participants in each of these categories was – bisexual/pansexual: 225; homosexual: 143; heterosexual: 3,161; asexual: 93; queer: 39 [10] The number of participants in each of these categories was – Black: 102; Caucasian: 2,023 [11] The number of participants in each of these categories was – USA: 865; worldwide: 3,858 [12] The number of participants in each of these categories in the USA was – Hispanic: 52; Black: 95; Caucasian: 653 [13] 46 survey participants worldwide identified as non-binary [14] Out of 921 true completers who had been in a clinical trial [15] Percentage numbers in all three points are out of 3,858 true completers [16] 2,903 participants had not been in a trial before; 921 participants had [17] Out of 3,858 true completers [18] Out of 170 true completers [19] Out of 897 true completers unwilling to participate in trials [20] Out of 3,858 true completers [21] Out of 2,227 people who identified as women [22] Out of 587 LGBTQ+ participants [23] Out of 102 black participants