February is African-American History Month or Black History Month, a tradition that in some form or another dates back to the United States in the 1920s and has since been adopted by countries across the world. As Black civil rights movements, including Black Lives Matters, in recent years have brought increased attention and awareness to a range of injustices, many companies, including Clariness, have increasingly begun to reflect on what can be done to improve equity and inclusion for those who identify as Black or African-American.*[1] With our Mission being “to improve patients’ lives by accelerating the development of new medical therapies,” we are committed to increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in clinical trials by taking a multilevel approach connecting patients, sponsors, and sites on our ClinLife patient portal. By engaging with Black/African-American patients, their communities, and other clinical trial stakeholders, as well as leveraging our 16+ years of experience with qualitative and quantitative data-driven outreach methods, we can connect more Black/African-American patients to clinical trials.

In this blog, we examine steps on how to improve the inclusion of Black/African-Americans in clinical trials:

- Diversity and improving representation in clinical trials

- What stops participation? Historical mistrust and mistreatment

- Digital outreach: Improving awareness and reducing distrust – where Clariness comes in

- Conclusion: Diversity and improving African-American representation in clinical trials

1. Diversity and improving representation in clinical trials

Most definitions of diversity in clinical research center around the “practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientation, etc.” Therefore, considering different backgrounds does not solely refer to the inclusion of a variety of racial, ethnic, or multicultural backgrounds, but also includes other demographic (e.g., sex, age, location of residence, socioeconomic status, etc.) and non-demographic (e.g., disabilities, comorbidities, genetics, concurrent medications, etc.) factors that all co-exist to form a person’s individual identity and experience.

Whereas low participation rates in clinical trials are an ongoing problem worldwide – causing almost 80% of clinical trials to be delayed (or to even fail) – minority populations, such as African-Americans, display even lower participation rates.[2] For example, whereas African-Americans make up 12% of the US population, they on average represent only 4 to 5% of all clinical trial participants.[3] Consequently, as researchers summarized in the journal Ethnicity and Disease, the underrepresentation of minorities in clinical research has a number of social and scientific implications and consequences:

“Lower participation rates among minority populations may compromise generalizability of research findings, raise concerns around biased reporting of adverse effects, and limit minorities from fully benefitting from research including access to cutting-edge therapies, thus contributing to racial health disparities.”

– Nadine J. Barrett, Kearston L. Ingraham et al. (2017).[4]

To further illustrate, while these figures vary slightly by indication, it is notable that underrepresentation occurs particularly in cancer and cardiology studies – diseases that disproportionately affect African-American patients. As of 2015, only 5% of participants in cancer trials were of African ancestry, while cancer death rates are 24% higher among African-American men and 14% higher among African-American women when compared to non-Hispanic whites.[5]

During Black History Month, historians have reiterated that major public health crises continue to affect minorities, and African-Americans in particular, in different and often disparate ways.[6] During previous health crises, such as the 1792-93 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia and the 1862-67 smallpox epidemic, African-Americans were disproportionately affected. Now, the COVID-19 crisis has again brought wide disparities in health outcomes of African-Americans to the forefront of the public debate, with the crisis often compared to the 1918 influenza pandemic. Historians noted an interesting paradox during the influenza where African-Americans had lower incidence and morbidity but higher mortality rates. In the current pandemic, researchers from Johns Hopkins University found that COVID-19 infection rates during the start of the pandemic were 3x higher in African-American neighborhoods than in predominantly white neighborhoods; and, in Chicago for example, >70% of COVID-19 deaths were African-Americans from just five neighborhoods, despite African-Americans only making up 30% of Chicago’s population.[7]

These disparities in health outcomes can be attributed to lower socioeconomic status and poorer access to public health facilities, as well as racial and outdated misconceptions among predominantly white healthcare professionals that (for example) Black patients may be “naturally immune,” which they obviously are not.[8] As a 2017 study published in Health Communication shows, implicit racial biases among non-Black physicians paired with a lower proportion of Black physicians (only 5.7% of physicians are Black) remains a major barrier to treatment and thus study participation for Black/African-American patients.[9]

2. What stops African-American participation? Historical mistrust and mistreatment

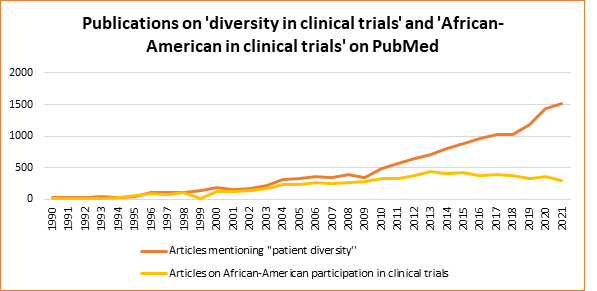

Since the 1990s, researchers have increasingly focused on increasing diversity in clinical trials (Figure 1). This is reflected in the number of articles addressing issues related to diversity and to the representation of African-Americans in clinical trial populations. While only about 200 articles were published on the topic of African-Americans and clinical trials in the entire 1990s, over 300 articles per year have been published in the last decade.[1]

In the literature addressing reasons for the underrepresentation of Black/African-Americans in clinical trials, 4 elements are typically addressed:

- Study design and representation

- Accessibility of clinical trials

- Awareness about clinical trials

- Distrust regarding clinical trial participation

1. Study design and representation

The protocol design of clinical trials is a major factor limiting the ability of many Black/African-American patients to participate, even when they are aware of clinical trials and willing to participate. In a joint statement in 2017, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research noted that Black cancer patients are more often excluded due to existing comorbidities and by predefined medical criteria.[2] For example, in prostate cancer studies, the inclusion criterion often states that testosterone levels must be <50 ng/dL, which ignores the fact that Black patients often have 15% higher testosterone levels compared to non-Hispanic white patients.[3] Another factor is that, particularly in the United States, clinical trial protocols often require participants to “use their insurance benefits for follow-up testing and specific treatments,” which may not be possible for African-Americans who are more likely to be uninsured.[4]

Other examples of barriers related to study protocols include:

- Birth control requirements: Clinical trials often require participants to take one or more methods of birth control. However, many African-American women do not have access to birth control, either because contraception is expensive, are not easily accessible without insurance, or because of a lack of general health/medical information.[5]

- Biological/group-specific conditions/diseases: Many clinical trial protocols are still shaped around a conceptualization of the study population that is predominantly white. For example, in cardiology trials for hypertension, one inclusion criterion sets the age of onset at 50 years old. However, as Dr. Jennifer Alvidrez of the U.S. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities notes, African-Americans usually develop this condition earlier and present with more severe disease by the age of 50.[6]

2. Accessibility of clinical trials

Researchers have pointed to several accessibility-related barriers faced by African-Americans, as well as for minority groups in general. Here, we define accessibility as a patient’s ability to access and reach clinical sites or research centers where clinical trials are conducted. One aspect that limits accessibility for African-Americans is site selection; for example, clinical trial organizers often select study sites primarily in large cities, at university hospitals, or in areas closer to predominantly non-Hispanic white neighborhoods. Additionally, African-American patients are less likely to have time and financial flexibility to take unpaid leave, find childcare, or pay for travel to the study center.[7] Since the median household income of African-Americans is nearly $20,000 lower compared to white Americans, these issues form a major barrier to participation. If clinical trial organizers were to provide compensation, it would likely remove a major barrier to participation in clinical trials.[8]

Some solutions include redesigning clinical trials to be more patient-centric including:

- Covering the cost of missed working days, childcare, and travel and stay at the study center, including higher compensation for attendance.

- Allowing flexible site visit hours or having fewer site visits

- Including decentralized and remote methods (e.g., remote monitoring, telehealth, mobile vans)

3. Awareness about clinical trials

Recent studies suggest that only a small proportion of clinical trial participants are actually referred by physicians, and this proportion is even lower for African-American patients. In addition, these patients are also more likely to be uninsured and, even if they are, to have access only to underserved hospitals and clinics that are unlikely to be chosen as clinical sites. This results in less clinical trial awareness and for these patients to potentially receive little or no information from their primary care physicians regarding other treatment options.[9] For example, in a recent study on the participation of Black women in breast cancer screening, the vast majority reported that their physicians had never informed them about breast cancer clinical trials.

Actions and interventions to improve clinical trial awareness among these communities include[10]:

- Community outreach programs and building relationships with community healthcare workers

- Creating accessible health literature

- Cultural competency training

- Providing information about clinical trials to research staff and physicians in predominantly African-American hospitals and clinics

4. Distrust regarding clinical trial participation

The history of medicine and clinical research is characterized by mistreatment and unethical experimentation on vulnerable people and minorities, including Black inidividuals in the United States. While many people inevitably think of the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972), in which hundreds of Black men were deprived of treatment for decades so that doctors could track their progression of syphilis, historians have shown that this was not an isolated case – but rather part of a long-term pattern.[11] These range from the 18th century smallpox experiments on Black slaves, to the so-called “father of genealogy,” J. Marion Sims, who performed coercive surgeries to study complications in childbirth. As Darcell P. Scharff et al. (2010) note in their review study, “More than Tuskegee: Understanding Mistrust about Research Participation,” African-American boys were enrolled in clinical trials as late as the 1990s that aimed to find the genetic cause of their “aggressive behavior.” Researchers even persuaded parents to let their sons participate in the study with the help of “monetary incentives,” even if it meant stopping their current medications (e.g., asthma), along with other ethical violations.[12]

As Stanford historian Londa Schiebinger notes in her recent book, Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the 18th-century Atlantic World (2017), tracing this history of mistreatment and showing its interconnectedness with the production of medical knowledge and medicine is critical to understanding and improving health disparities today. To include more Black/African-Americans patients into clinical trials and to ensure medicines are effective in all patients, it is critical to recognize and acknowledge the impact and ways in which these historical events and processes have, and continue, to shape the present issues. Only then can the barriers faced by these communities be successfully broken down. However, it is important that the recognition of historical wrongdoing goes beyond mere “performative apologies” and leads to an active recognition of today’s barriers and institutions underlying inequalities in health.

As Karen Lincoln, professor of social work at USC and founder of Advocates for African American Elders explains:

“If you continue to use [Tuskegee] as a way of explaining why more African Americans are hesitant, it almost absolves you of having to learn more, do more, involve other people – admit that racism is actually a thing today.” [13]

Thus, to combat distrust towards participating in clinical trials, it is important to address certain misconceptions by being transparent, providing additional health/medical information, sharing the perspectives of people from Black/African-American communities, and working with community leaders and centers. Although, some, including Alvidrez, go so far as to say that while it is important to address historical mistrust, “the idea that minorities might be mistrusted is actually a bigger barrier.”

“Studies on willingness [to participate in clinical trials] find that there isn’t a difference between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites, but whites are much more likely to be approached.”

– Jennifer Alvidrez of the U.S. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

To consider:

- Improve trust through outreach efforts: the majority of African-Americans still cite distrust as a primary barrier to participation in clinical trials.[14]

- Health literacy is crucial to understanding clinical trials and building trust: According to some studies, African-Americans have lower health literacy levels compared to non-Hispanic Whites.[15] Furthermore, Es Hamel et al. (2016) found that African-Americans may be given missing or unclear information leading them to believe that trial consent forms serve to “protect hospitals and doctors from any legal responsibility,” rather than to help them understand the clinical trial and to make an informed decision

3. Digital outreach: Improving awareness and reducing distrust – where Clariness comes in

At Clariness, our Mission is “to improve patients’ lives by accelerating the development of new medical therapies.” To do this, we take a multilevel approach connecting patients, sponsors, and sites on our ClinLife patient portal. As a diverse company, with people located worldwide and speaking over 35 languages, we understand and are committed to overcoming barriers to diversity in clinical trials. With growing health disparities, we are motivated to help sponsors improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in clinical trials through patient engagement.

We believe that a combination of quantitative and qualitative data-driven and patient-centric approaches to patient recruitment can accelerate the way towards more inclusive and representative clinical trials. By doing digital outreach, we can reach people who fall outside of the healthcare system, which pertains especially African-Americans in the United States. Furthermore, digital outreach methods when applied right can reach patients living within a predesignated radius around active sites and base its outreach on the incidence of the indication. We also perform local population analyses around study sites to provide insights on study sites selection to improve the inclusion of African-American, and other underrepresented, communities. For example, diabetes prevalence, varies from region to region in the US, with a higher incidence in the southern states and in African-American patients. As similar trends in geographic differences in prevalence compared to demographics are also observed across other regions of the world, we adapt our global data-driven outreach to local conditions and specific indications.

4. Conclusion: improving African-American representation in clinical trials

Improving digital outreach to Black/African-American patients represents only one aspect of addressing barriers to trial participation within these communities. Clinical trial sponsors, along with other clinical trial stakeholders, need to take a multilevel approach tailored to specific indications and local regions. At Clariness, we implement several initiatives to spark change, including:

- Health literacy: One way to overcome key barriers to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in clinical trials is to improve health literacy and communication. With 58% of African-Americans having basic or below basic health literacy, compared with 28% of non-Hispanic whites, it is (for example) important to make advertisements in easily understandable non-scientific language. In 2021, we launched our new patient blog initiative in Germany and Poland, where we provide straightforward information about clinical research and procedures, as well as safety and ethical checks to address general and group-specific concerns.

- Accessibility and inclusion: Our Creatives Team ensures that each study and recruitment material is accessible (language, wording, and design), uses diverse images, and are translated into local languages. We also work with language experts to use inclusive language – particularly regarding gender-neutral and gender-inclusive terms (e.g., pronouns).

- Patient engagement: We use social media to engage with patients by answering questions or providing information regarding health and clinical trials. More recently, we’ve partnered with sponsors to create websites for specific studies with study-related and health-related information.

- Patient support: With African-American drop-out and lost to follow up being significantly higher then non-Hispanic white participants, it is crucial to take measures to reduce this gap.[1] To improve patient retention, we offer intensified support communicating regularly with patients to help them schedule visits and set up reminders. This helps to keep patients engaged and troubleshoot any issues quickly.

This blog has highlighted how the problem of improving Black/African-American participation in clinical trials has a long history where inequality, racism, and problematic and unethical clinical research have been intertwined. However, recognition of this history should be framed with a focus on how it affects present processes. Tackling barriers to minority participation, including Black/African-Americans, requires a nuanced approach and understanding of past and current issues to clinical trial access and participation. In this blog, we have discussed some of these barriers, as well as some possible short-term and long-term solutions (e.g., re-evaluating I/E criteria, digital outreach, diverse staff, improving health literacy).

As a patient recruitment company, we can reach and inform patients about clinical trial options to help make clinical trials more acessible, diverse, and representative to ensure that medicines and therapies are safe and effective for all patients. We work with patient organizations and clinical trial stakeholders to adapt every facet of clinical trials in a way that improves DEI. Contact us if you have questions on improving DEI in your clinical trials.

Recommended reading

Otado J, Kwagyan J, Edwards D, Ukaegbu A, Rockcliffe F, Osafo N. Culturally Competent Strategies for Recruitment and Retention of African American Populations into Clinical Trials. Clin Transl Sci. 2015 Oct;8(5):460-6. doi: 10.1111/cts.12285. Epub 2015 May 14. PMID: 25974328; PMCID: PMC4626379. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25974328/

[1] Ginsburg KB, Auffenberg GB, Qi J, Powell IJ, Linsell SM, Montie JE, Miller DC, Cher ML. Risk of Becoming Lost to Follow-up During Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2018 Dec;74(6):704-707.

Part I.

[1] This blog refers to those who identify as Black and/or African-American. For readability, the terms may be used interchangeably in some parts.

[2] Clinical trials Arena, ”Clinical trial delays: America’s patient recruitment dilemma”, (2012) https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/marketdata/featureclinical-trial-patient-recruitment/

[3] Clark LT, Watkins L, Piña IL, Elmer M, Akinboboye O, Gorham M, Jamerson B, McCullough C, Pierre C, Polis AB, Puckrein G, Regnante JM. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2019 May;44(5):148-172.

[4] Barrett NJ, Ingraham KL, Vann Hawkins T, Moorman PG. Engaging African Americans in Research: The Recruiter’s Perspective. Ethn Dis. 2017 Dec 7;27(4):453-462. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29225447/

Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2016-2018 American Cancer Society https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2016-2018.pdf

[6] Patterson GE, McIntyre KM, Clough HE, Rushton J. Societal Impacts of Pandemics: Comparing COVID-19 With History to Focus Our Response. Front Public Health. 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8072022/

[7] Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020 May 19;323(19):1891-1892. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32293639/

[8] Økland H, Mamelund SE. Race and 1918 Influenza Pandemic in the United States: A Review of the Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 12;16(14):2487 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31336864/

[9] Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-e76. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4638275/

Part II

[1] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=African-American+clinical+trial&filter=years.1991-2022

[3] Hu H, Odedina FT, Reams RR, Lissaker CT, Xu X. Racial Differences in Age-Related Variations of Testosterone Levels Among US Males: Potential Implications for Prostate Cancer and Personalized Medication. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015 Mar;2(1):69-76. And Ross R, Bernstein L, Judd H, et al: Serum testosterone levels in healthy young black and white men. J Natl Cancer Inst 76:45-48, 1986 Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, et al: Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research statement. J Clin Oncol 35:3737-3744, 2017

[4] Awidi M, Al Hadidi S. Participation of Black Americans in Cancer Clinical Trials: Current Challenges and Proposed Solutions. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021 May;17(5):265-271.

[5] Michican News, ‘Water, water everywhere, but not a drop to drink: Black women face a ‘contraceptive desert’, (2019) https://news.umich.edu/water-water-everywhere-but-not-a-drop-to-drink-black-women-face-a-contraceptive-desert/

[6] S&P Global, ‘For African Americans, clinical trial exclusion reflects institutional biases’, (2019)

[7] Diehl KM, Green EM, Weinberg A, et al: Features associated with successful recruitment of diverse patients onto cancer clinical trials: Report from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3544-3550, 2011

[8] Diehl KM, Green EM, Weinberg A, et al: Features associated with successful recruitment of diverse patients onto cancer clinical trials: Report from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3544-3550, 2011

[9] Barrett NJ, Ingraham KL, Vann Hawkins T, Moorman PG. Engaging African Americans in Research: The Recruiter’s Perspective. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(4):453-462. Published 2017 Dec 7. doi:10.18865/ed.27.4.453 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5720956/

[10] George S. Duran N. , & Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e16–e31. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301706

[11] Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879-897. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0323 https://news.stanford.edu/2017/08/10/medical-experimentation-slaves-18th-century-caribbean-colonies/

[12] Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879-897. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0323

[13] Dembosky, A., ‘Stop Blaming Tuskegee, Critics Say. It’s Not An ‘Excuse’ For Current Medical Racism’, (2021)

[14] Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Heath E, Gwede CK, Eggly S. Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment in Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients With Cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):327-337. doi:10.1177/107327481602300404

[15] Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Heath E, Gwede CK, Eggly S. Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment in Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients With Cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):327-337. doi:10.1177/107327481602300404